The Doctor is Out

- Jonathan Kalb

- Jun 27, 2023

- 4 min read

The 37-year-old British directing star Robert Icke—whose The Doctor is playing at the Park Avenue Armory until mid August—has become something of a New York regular, hosted in our plushest venues and touted as a sort of de facto heir to the now-aging classics-reinventors Ivo van Hove and Thomas Ostermeier. (They are the only other European director-bad-boys to meaningfully crack the New York scene in our era.) With four splashy shows at the Armory since the pandemic closure—An Enemy of the People, Hamlet, The Oresteia and The Doctor—and a Broadway production in 2017 (1984), Icke is certainly the producer’s darling of the moment.

Yet the quality of these shows has been mixed, with vivid acting and bold, thoughtful intentions competing with woolly, sometimes implausible scripts and overdone media effects. The Doctor is another mixed bag of this sort, crucially brightened, I’m happy to say, by a searing lead performance by Juliet Stevenson. Among the Icke shows I’ve seen, it’s most comparable to Hamlet, which was also rescued from conceptual confusion by an amazing lead performance.

The Doctor is Icke’s very loose adaptation of Arthur Schnitzler’s 1912 Professor Bernhardi, a modern classic produced regularly by the Germans (6 German films have been made of it) but almost never seen on English-language stages. Often compared with An Enemy of the People—Ibsen’s corrosive 1882 tale of an idealistic physician railroaded by his esteemed neighbors after blowing the whistle on toxic spa water—Professor Bernhardi is about a Jewish doctor condemned for preventing a priest from giving last rites to a young woman dying of sepsis after a botched abortion. Bernhardi fiercely defends his actions as medically necessary (the dazed woman had to be allowed to die without the priest terrifying her) and is beset with anti-Semitic outrage in Catholic Vienna.

Both Ibsen’s and Schnitzler’s plays are ripe for revival in this post-factual era because both are about toxic collisions of science and politically manipulated mass opinion. Enemy has been downright ubiquitous of late, with recent versions in New York by Doug Hughes, Jeff Wise, Ostermeier and Icke, and yet another starring Jeremy Strong announced for Broadway next year. Professor Bernhardi, by contrast, is a unicorn. I’ve never seen a professional production of it in the U.S.

Icke follows Schnitzler’s plot setup fairly closely for an hour or so—famous Jewish doctor scandalously thwarts priest—and then goes his own way. The best reason to see The Doctor is Stevenson’s typhoon of a performance as the title character, Dr. Ruth Wolff—a proud, tightly wound, brusquely imperious taskmaster who runs an Alzheimer research institute and finds herself humbled by the brouhaha she foments. The portrait of an aggressive female in a power position may remind some of Cate Blanchett in Tar. In the end Ruth is forced to evolve into a reluctantly reflective observer, shocked by the destruction she sets in motion, a transformation Stevenson makes unforgettably visceral and disturbing.

This is a rich, compelling, and worthwhile story arc—different from Schnitzler’s but so what?—that I wish Icke had trusted enough to stick with and build his play around.

Instead, he treats Ruth’s story as a scaffold to hang sundry peripheral political issues on, which ends up overpacking the play with topical detritus. Ruth’s intransigence is interesting. She’s asked by reasonable colleagues to simply neutralize the scandal with a pro-forma apology but her severe ethical compass won’t allow it. Does her rigidity amount to virtue, conscience, righteous arrogance? Icke unfortunately squanders our curiosity about what it might be, offering only disconnected, ambiguous teases and half-facts about her backstory instead of substantial information.

Her old lover Charlie (Juliet Garricks), for instance, wafts in and out and may be dead, and a lonely neighbor kid named Sami (Matilda Tucker) hangs out at her house for unclear reasons. What are Ruth’s emotional connections with these people? What do they really mean to her? And how did she develop such uncharacteristic softness towards them? We never know because Icke isn’t really interested.

Much of the nearly 3-hour play is consumed with shouted institutional arguments around conference tables, with every speech treated as a monumental climax. These faux-climaxes grow tiring very quickly. Variation of a sort arrives about 2 hours in when the venue for shouting shifts to TV (Icke really can’t resist media sequences). Ruth is grilled on air by a panel of trollish “experts” plainly chosen to represent a laundry list of today’s touchiest activist positions, each with its own strident take on racial representation, gender identity, creationism, abortion politics, Jewish history, postcolonialism, white privilege, unconscious bias, what have you. The panelists hector her in a beat-down whose point seems to be to set her up to rage heroically against group identity of all kinds, preferring the sort of universal humanity that medicine respects.

What I can’t abide is this endless dividing up of people into tribes and smaller tribes of smaller tribes. You cut humanity in half enough times, eventually it ceases to exist.

It’s hardly surprising that no heroes can emerge in such a forum because the media itself sucks up all the oxygen, reducing even passionate exchanges to a values-free circus.

My impression is that Icke convinced himself that this media circus could serve as a collective villain in his play, reading as a sort of monolith of woke intolerance. The idea doesn’t track, though. The production’s casting, for instance, is as woke as it gets. All roles were evidently cast race- and gender-blind, preventing us from knowing at a glance what any character’s group identity is: women play men, men women, Blacks play whites and the other way round. We even eventually learn that the priest, played by a white actor (John Mackay), is Black—a late reveal used to underscore why Ruth shouldn’t have confronted him so imperiously. Your feelings about that reveal will very likely parallel your feelings about Ruth’s overall dramatic portrait.

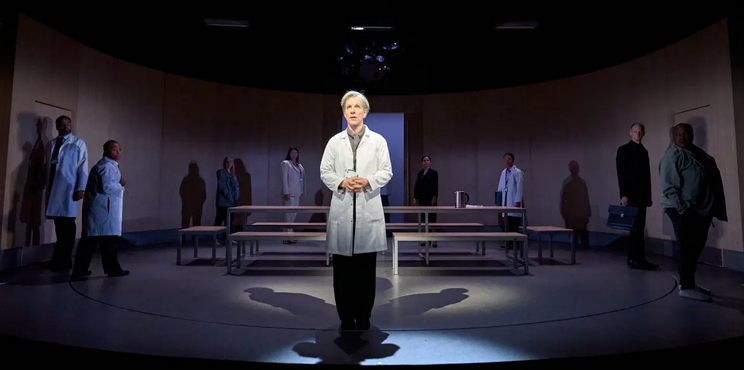

All of this aside, I nevertheless loved Hildegard Bechtler’s set for the show. Its main feature is a cold, wide, semicircular, wooden wall encompassing the playing space. Lit variously, this arena can be made to feel folksy-homey, brutalist-impersonal, pleasantly open, or oppressively insular. At one point, after learning that her institute’s board has thrown her under the bus to save itself (prodded by her opportunistic Catholic rivals), Ruth suddenly sheds her white doctor’s coat and runs furious laps around this wall, vaguely like a gladiator fleeing a beast. It’s a striking sequence—startling, jarringly physical, weirdly prolonged. In the back of my mind while watching it, though, my stray thought was: remind me what’s chasing her again?

Photos: Stephanie Berger

Written and directed by Robert Icke

Park Avenue Armory

Comments